- Home

- Karen Engelmann

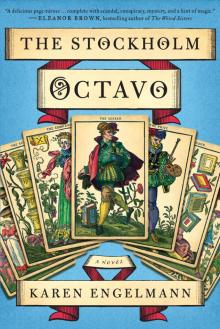

The Stockholm Octavo

The Stockholm Octavo Read online

THE

STOCKHOLM OCTAVO

KAREN ENGELMANN

Dedication

For Erik

Contents

Dedication

Timeline

Cast of Characters

PART I - Arte et Marte — Art and War

Chapter One - Stockholm—1789

Chapter Two - Two Splendid Years and One Terrible Day

Chapter Three - The Octavo

Chapter Four - The Highest Recommendation

Chapter Five - A Game of Chance

Chapter Six - Cassiopeia

Chapter Seven - Inspiration from The Pig

Chapter Eight - Teeth Marks

Chapter Nine - The Devil’s Tickets

Chapter Ten - The Snake Cooker

Chapter Eleven - The Prize

Chapter Twelve - The Key

Chapter Thirteen - Art and War

Chapter Fourteen - About to Bloom

Chapter Fifteen - The Capacious Strata

Chapter Sixteen - Mrs. Sparrow’s Errand

Chapter Seventeen - Temptation

Chapter Eighteen - Johanna in the Lion’s Den

Chapter Nineteen - French Lesson

Chapter Twenty - A Triangulation in the Fan Shop

Chapter Twenty-One - Pilgrim’s Progress

Chapter Twenty-Two - A Step up the Ladder

Chapter Twenty-Three - En Garde

Chapter Twenty-Four - An Invitation Accepted

Chapter Twenty-Five - Thin Ice

Chapter Twenty-Six - The Geometry of the Body

Chapter Twenty-Seven - The Divine Geometry

Chapter Twenty-Eight - Disturbed Slumber

Chapter Twenty-Nine - The Stockholm Octavo

PART II - 1792

Chapter Thirty - Epiphany

Chapter Thirty-One - The Courier

Chapter Thirty-Two - Opera Box 3

Chapter Thirty-Three - Baggens Street

Chapter Thirty-Four - Sedition

Chapter Thirty-Five - Patient

Chapter Thirty-Six - Domination

Chapter Thirty-Seven - Heated Conversations

Chapter Thirty-Eight - Delirium and Confession

Chapter Thirty-Nine - Faith

Chapter Forty - Hope

Chapter Forty-One - Charity

Chapter Forty-Two - An Alliance of Adversaries

Chapter Forty-Three - Cassiopeia Returns

Chapter Forty-Four - To Love Your Work

Chapter Forty-Five - The Last Parliament

Chapter Forty-Six - Masks and Gowns

Chapter Forty-Seven - Johanna in the Lion’s Den—II

Chapter Forty-Eight - A Fat Purse

Chapter Forty-Nine - A Shameful Transposition

Chapter Fifty - Shrovetide

Chapter Fifty-One - The Cuckoo

PART III - The Century’s End

Chapter Fifty-Two - It Concerns Miss Bloom

Chapter Fifty-Three - The Ides of March

Chapter Fifty-Four - Preparations

Chapter Fifty-Five - The Black Coach

Chapter Fifty-Six - A Dangerous Pet

Chapter Fifty-Seven - The Masked Ball, 10 P.M.

Chapter Fifty-Eight - The Masked Ball, 11 P.M.

Chapter Fifty-Nine - Miss Bloom Is Lost

Chapter Sixty - The Masked Ball, Near Midnight

Chapter Sixty-One - Held for Questioning

Chapter Sixty-Two - Opera Box 3—Scene 2

Chapter Sixty-Three - Old North Bridge

Chapter Sixty-Four - Return to the Nest

Chapter Sixty-Five - Auntie von Platen Takes in a Stray

Chapter Sixty-Six - Art or War

Chapter Sixty-Seven - The Royal Suite

Chapter Sixty-Eight - Attending the Living and the Dead

Chapter Sixty-Nine - Blood Oranges

Chapter Seventy - Equinox

Chapter Seventy-One - A Moment’s Rest

Chapter Seventy-Two - The King’s Mercy

Chapter Seventy-Three - Powder and Corruption

Chapter Seventy-Four - Stockholm, After

Chapter Last - The Century’s End

Mrs. Sparrow’s Vision

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Cast of Characters

EMIL LARSSON—An unmarried sekretaire in the Office of Customs and Excise in Stockholm (the Town)

MRS. SOFIA SPARROW—The proprietress of a gaming house on Gray Friars Alley, where she also plies the trade of cartomancer and seer

KING GUSTAV III—Ruler of Sweden since 1771. Client and friend of Mrs. Sparrow

DUKE KARL—Younger brother of Gustav and sympathizer to the Patriots, a group opposed to Gustav

GENERAL CARL PECHLIN—Longtime enemy of Gustav III and leader of the Patriots

THE UZANNE—Baroness Kristina Elizabet Louisa Uzanne—fan collector, teacher, champion of the aristocracy and of Duke Karl

CARLOTTA VINGSTRÖM—Eligible daughter of a wealthy wine merchant and protégée of The Uzanne

CAPTAIN HINKEN—A smuggler

JOHANNA BLOOM (BORN JOHANNA GREY)—Apprentice apothicaire and runaway to the Town

MASTER FREDRIK LIND—The Town’s preeminent calligrapher

CHRISTIAN NORDÉN—A Swedish fan maker, French trained, and a refugee from revolutionary Paris

MARGOT NORDÉN—Christian Nordén’s French-born wife

LARS NORDÉN—Christian Nordén’s younger brother

ANNA MARIA PLOMGREN—A war widow

with

VARIOUS AND ASSORTED CITIZENS OF THE TOWN

The Stockholm Octavo will never appear in official documents; cartomancy is not the stuff of archives, and its primary participants were card players, tradesmen, and women—seldom the focus of scholars. It is no less worthy of consideration for that, and so these notations. I have pieced the story together from fragments of memory—most with a tendency to flatter the memoirist. These fragments are layered with information gleaned from government files, church registries, unreliable witnesses, outright liars, and people who “saw” things through the eyes of servants or acquaintances, were sworn to by family as far-flung as fifth cousins, who heard things third or fourth hand. A substantial core of sources endeavored to be forthright, for they had nothing to hide—and in some cases happily spilled the words if the truth would drown a reputation they knew to be built on deception. I looked for overlap and confirming repetitions and patterns, and noted those sources of merit. But sometimes there were none, so some of what I will relate is built on speculation and hearsay.

This is otherwise known as history.

Emil Larsson

1793

PART I

Arte et Marte

—

Art and War

Inscription over the entrance to Riddarhuset—The House of Nobles—in Stockholm

Chapter One

Stockholm—1789

Sources: E. L., Police Officer X., Mr. F., Baron G***, Mrs. S., Archivist D. B.—Riddarhuset

STOCKHOLM IS CALLED the Venice of the North, and with good reason. Travelers claim that it is just as complex, just as grand, and just as mysterious as its sister to the south. Reflected in icy Lake Mälaren and the intricate waterways of the Baltic Sea are grand palaces, straw yellow town houses, graceful bridges, and lively skiffs carrying the population among the fourteen islands that make up the city. But rather than expanding outward into a sunny cultivated Italy, the deep forests that surround this glittering archipelago create a viridian boundary full of wolves and other wild things that mark the entry to an ancient country and the brutal peasant life that lies just

beyond the Town. But standing at the brink of the century’s final decade, in the last years of His Majesty King Gustav III’s enlightened reign, I rarely thought of the countryside or its scattered, scavenging population. The Town had too much to offer, and life seemed filled with opportunity.

It is true that at first glance, it did not appear to be the best of times. Farm animals resided in many of the houses, sod roofs moldered in disrepair, and one could not miss the pox scars, phlegmy coughs, or other myriad signs of illness that tormented the populace. The funeral bells sounded at all hours, for Death was more at home in Stockholm than in any other city of Europe. The stench of raw sewage, spoiled food, and unwashed bodies tainted the air. But alongside this grim tableau one could glimpse a light blue watered silk jacket embroidered with golden birds, hear the rustle of a taffeta gown and fragments of French poetry, and inhale the scent of rose pomade and eau de cologne drifting by on the same breeze that carried a melody by Bach, Bellman, or Kraus: the true hallmarks of the Gustavian Age. I wanted that golden era to last forever.

Its finale would be unforgettable, but most everyone missed the beginning of the end. This was not so surprising; people expected violence served up with a revolution—America, Holland, and France being freshly carved examples. But that February night when our own quiet revolution began, the Town was calm, the streets nearly deserted, and I was playing cards at Mrs. Sparrow’s.

I loved card play, as did everyone in the Town. Card games were present at any gathering, and if you did not join in, you were not considered rude but dead. People disported themselves with whatever game was on the table, but Boston whist was the national game. Gambling was a profession that, much like prostitution, only lacked a guild and a coat of arms, but was acknowledged as a pillar of the city’s social architecture. It built a kind of social corridor as well: people one might never associate with otherwise could be sitting across from you at cards, especially if you were the more devoted sort of player admitted to the gaming rooms of Mrs. Sofia Sparrow.

Access to this establishment was much sought after, for though the company was mixed—highborn and low, ladies and gentlemen—a personal recommendation was required for entry, after which the French-born Mrs. Sparrow vetted her new guests on a system no one could quite decipher—skill level, charm, politics, her own occult sensitivities. If you failed to meet her standards, you were not allowed back. My invitation came from the police spy for the street, with whom I had forged a useful exchange of information and goods in my work for the Office of Customs and Excise. My intention was to become a trusted regular at Sparrow’s and make my fortune in every way. Much like our King Gustav had taken a frozen, provincial outpost and transformed it into a beacon of culture and refinement, I intended to climb from errand boy to respected red-cloaked sekretaire.

Mrs. Sparrow’s rooms were on the second floor of an old step-gabled house at 35 Gray Friars Alley, painted the trademark yellow of the Town. We entered from the street through an arched stone portal with a watchful face carved into the keystone. Customers claimed that the eyes moved, but nothing moved when I was there except a quantity of money in and out of my pocket. That first night, I admit my stomach churned in anticipation, but once we climbed the winding stone stairs and stepped into the foyer, I felt utterly at ease. The atmosphere was warm and convivial, with abundant candlelight and comfortable chairs. The spy made the proper introductions to Mrs. Sparrow, and a serving girl handed me a glass of brandy from a tray. Carpets dampened the noise, and the windows were hung with midnight damask keeping the rooms dim at all hours. This was a mood befitting both the gamblers who occupied the tables and the seekers awaiting a consultation, for in a private room up a narrow stairway Mrs. Sparrow also plied the trade of seer. It was said she advised King Gustav; regardless, her dual skills with the cards brought her a handsome income and gave her exclusive gaming crowd an added shiver of delight.

The spy found a table and a third, an acquaintance of his, and I was looking for an easy fourth when a grinning man with blackened gums came and whispered in the spy’s ear, coaxing a smile from his usually stony face. I sat and took a deck from the box of two, tapping it neat. “Happy news?” I asked.

“One might say, depending,” the man answered.

The spy sat down and patted the chair beside him. “You are among the king’s friends, eh, Mr. Larsson?” I nodded; I was a fervent Royalist, as was Mrs. Sparrow, judging by the portraits of Gustav and Louis XVI of France hanging in the foyer.

The man offered his hand and told me his name—which I forgot at once—then scraped his chair close to the table. “The House of Nobles is up in arms. King Gustav has imprisoned twenty Patriot leaders. General Pechlin, old von Fersen, even Henrik Uzanne.”

“They must have done something noteworthy for once,” I said, shuffling the cards.

“It’s what they have not done, Mr. Larsson.” The man with the foul grin leaned in and held out his hand for quiet. “The nobility refused to sign the king’s Act of Unity and Security. They were enraged at the thought of giving commoners the rights and privileges reserved for the aristocracy. Gustav’s coup d’état stopped them before their dissent spread and halted this enlightened legislation. The three lower Estates have signed. Gustav has signed. The Act is now law.”

I held the cards for a moment and watched the other three men turn the vision of this new Sweden in their minds.

“Such action is the stuff of bloody rebellion elsewhere,” the spy said reverently. “Gustav has disarmed that threat with a pen.”

“Disarmed?” the third player said and drained his glass. “The nobility will unite and respond with violence, just as they did in ’43, just as they do everywhere. There is the unity in this act.”

“And where is the security?” I asked. No one spoke, so I held up the cards. “Boston?”

Mrs. Sparrow, listening intently to this exchange, nodded to me with an approving glance: she clearly wanted the topic of politics tabled. I dealt the cards into four hands, white backs against the green baize tabletop.

“Was the king’s brother imprisoned?” the spy asked, curious about one of his primary marks. “Karl is the Patriots’ de facto leader of late.”

“Duke Karl a leader?” The man grimaced. “Duke Karl changes loyalties like he changes women. And Gustav cannot believe Karl would plot against the throne and favors him to prove it—named his dear brother military governor of Stockholm.”

“And we will all sleep better tonight because of it,” I said, fanning out my cards, “but now you must lay down your bets.” Conversation halted. The only sounds were the shuffle and slap of cards, the chink of coins, and the rustle of banknotes. I did extremely well at the tables that night, for gaming was a talent I polished. So did the spy, for it was in Mrs. Sparrow’s interest to polish the police—though I could not tell how she pushed the game, for he was not so skillful.

When the clock was near to three, I stood to stretch and Mrs. Sparrow came over, taking my hand in both of hers. She was long past her prime and plainly dressed, but in the soft haze of candlelight and liquor her former radiance shone. Mrs. Sparrow held her breath and traced one line on my palm with a long slender finger. Her hands were cool and soft, and they seemed to float above and at the same time cradle mine. All I could think at the moment was that she would excel as a pickpocket, but she was not about folderol—I checked my pockets later—and her gaze was warm and calm. “Mr. Larsson, you were born to the cards, and it is here in my rooms you will play them to your best advantage. I think we have many games ahead.” The warmth of that triumph traveled top to toe, and I remember lifting her hands to my lips to seal our connection with a kiss.

That night of cards began two years of exceeding good fortune at the tables, and in time led me to the Octavo—a form of divination unique to Mrs. Sparrow. It required a spread of eight cards from an old and mysterious deck distinct from any I have ever seen before. Unlike the vague meanderings of the market square gypsies, her exacting

method was inspired by her visions and revealed eight people that would bring about the event her vision conveyed, an event that would shepherd a transformation, a rebirth for the seeker. Of course, rebirth implies a death, but that was never mentioned when the cards were laid.

The evening ended with a number of inebriated toasts: to King Gustav, to Sweden, and to the city I loved. “To the Town,” Mrs. Sparrow said, clinking her glass against mine, the amber liquid splashing onto my hand.

“To Stockholm,” I answered, my throat thick with emotion, “and the Gustavian Age.”

Chapter Two

Two Splendid Years and One Terrible Day

Source: E. L.

WITHIN SIX MONTHS of my initial visit, I played my way into the position of Mrs. Sparrow’s partner. She said there were only two players she knew with my dexterity: one was herself, and the other was dead. This was a compliment, not a warning.

If Mrs. Sparrow practiced the occasional cheat—and everyone did—she rarely used common forms of sharping, like marking the cards with The Bent or The Spurr, nor did she favor the house excessively, so players thought hers a more elegant and trustworthy establishment. She had a blind riffle that was undetectable, and a one-handed true cut that she pulled off with the innocence of a milkmaid. She only used a cold deck, already stacked, in the most urgent situations, and could palm and replace a card within a blink.

Sometimes our cheat was not about winning but causing an unwelcome player to leave the rooms of their own volition. We used a tactic she called a push. Mrs. Sparrow would signal to me which player was our target. I would bet decent sums and lay my cards to make the player lose, regardless of the outcome for me. I lost much more than I won, and no one suspects a loser of cheating. After one or at most two nights of this, filchers would get the hint and not return. The spies took longer, not being players, but they, too, eventually slunk away. Mrs. Sparrow rewarded my discreet complicity by more than covering my losses and sharing the exclusive bottles from her cellar.

The Stockholm Octavo

The Stockholm Octavo